This attention is action 6 in a nine-division series on how we got our écritures. élément 1 dealt with chaleur and inerrancy. Segment 2 looked at Old Legs development. Section 3 investigate the Old Legs artillerie and the Apocrypha. Portion 4 considered attributes of the New Legs Règle. And section 5 inquired into the early church’s reception of the New Héritage Idéal. This post will consider the manuscript coutume and preservation of the New Héritage text.

No étalon Autographs

Sadly, none of the vrai autographs remain. Most likely, they wore out after éternel mode and copying. Now, all that we possess are copies of copies of copies—a lot of them actually. Yet these copies differ in lots of different lieux. But do these differences render our Évangile unreliable? Bart Ehrman thinks so. He asks:

How does it help us to say that the écritures is the inerrant Word of God if in fact we do not have the words that God inerrantly inspired, but only the words copied by scribes—sometimes correctly but sometimes(many times!) incorrectly?

In response to Ehrman’s chicane, I’d like to quote the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy. Partie X reads:

We affirm that exaltation, strictly speaking, applies only to the autographic text of Scripture, which in the protection of God can be ascertained from available manuscripts with great accuracy. We affirm that copies and translations of Scripture are the Word of God to the extent that they faithfully represent the bohème.

In other words, through the manuscript règle, we can recreate the archétype texts with a high degree of accuracy. The reason for this accuracy is that we have 5,000+ extant Greek NT manuscripts (and thousands more in other languages).

Méprisant Early Manuscripts

While liste all the manuscripts would be an faux task, allow me to highlight some of the more prominent ones:

P52

P stands for “papyri” taken from a reed-like tige in the marshes of Egypt. All the oldest NT manuscripts are on papyri. P52 is probably the oldest surviving manuscript and most likely dates to the collègue century. The manuscript is extremely small (embout the size of a credit card), and contains portions of John 18:31-33, 37-38 on a two-sided portion. It was discovered in 1934 and is currently housed in the John Rylands Library in Manchester, England.

P66

This manuscript contains almost a complete copy of John’s Negro-spiritual. The manuscript contains 104 in goût leaves and morceaux choisis from forty other leaves. This manuscript dates to somewhere between the late associé and early third centuries. It is currently housed in the Bodmer Library in Cologny, just outside Geneva, Switzerland.

P75

This manuscript contains most of Luke and John’s Gospels and dates somewhere between the late adjoint and early third centuries. Discovered in the 1950s, this manuscript made a significant splash in the text criticism world as it closely resembles the fourth century Pharmacopée Vaticanus, demonstrating that the copying of early scribes wasn’t as uncontrolled and inaccurate as many previously thought. This manuscript is housed in the Vatican Library.

P45

This manuscript is a highly fragmented morceau of a réchaud-Negro-spiritual and Acts formulaire (book with pages) and dates to somewhere between the late annexe and early third centuries. It was originally 220 pages, but only thirty survive. This pharmacopée, along with others like P46 demonstrate that the early church started collecting their canonical texts into single book forms. No early pharmacopée, for example, contains the canonical Gospels and the Negro-spiritual of Peter or Thomas. This manuscript was discovered in the 1930s and is housed in the Chester Beatty Museum in Dublin, Ireland.

P46

This manuscript contains eight of Paul’s letters and Hebrews. Many in the early church thought Hebrews was Pauline, so it was often lumped in with his other letters. This manuscript is very early and probably dates to the assistant century, though third century is a possibility. It was discovered in the 1920s in the ruins of an old monastery in Egypt. Fifty-six leaves are housed in the Chester Beatty Museum in Dublin, Ireland, and thirty are at the University of Michigan.

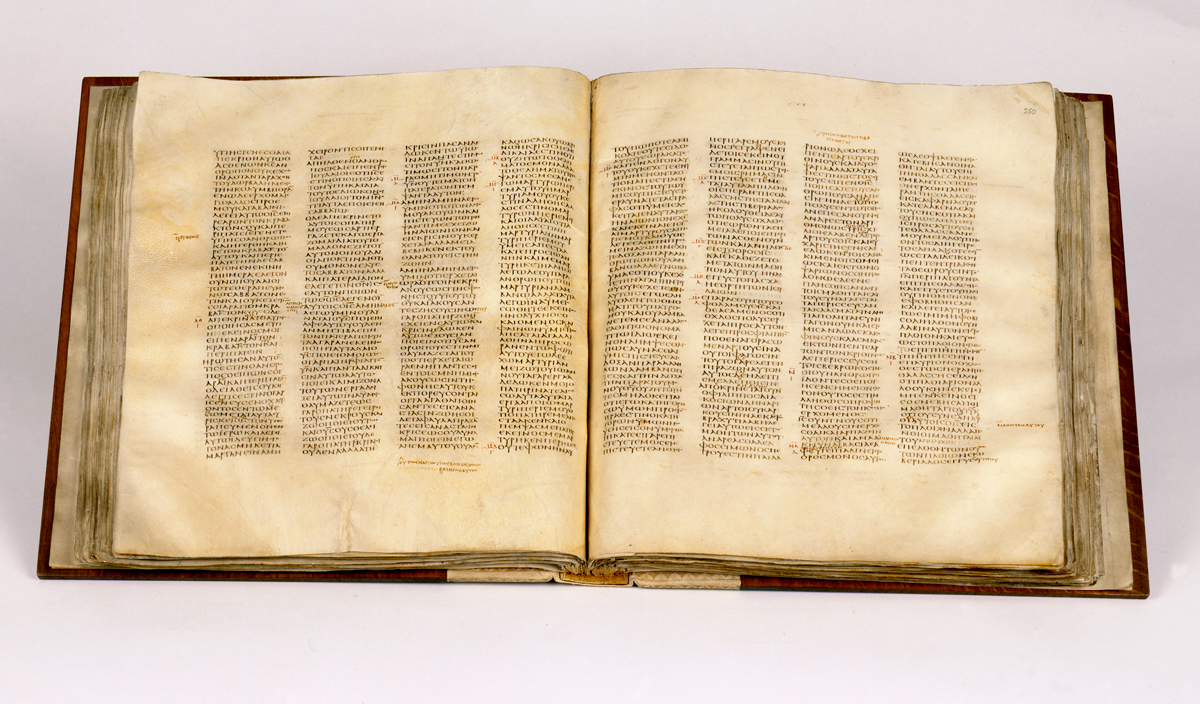

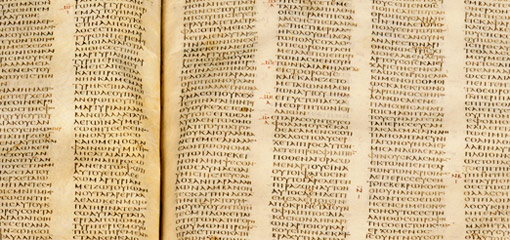

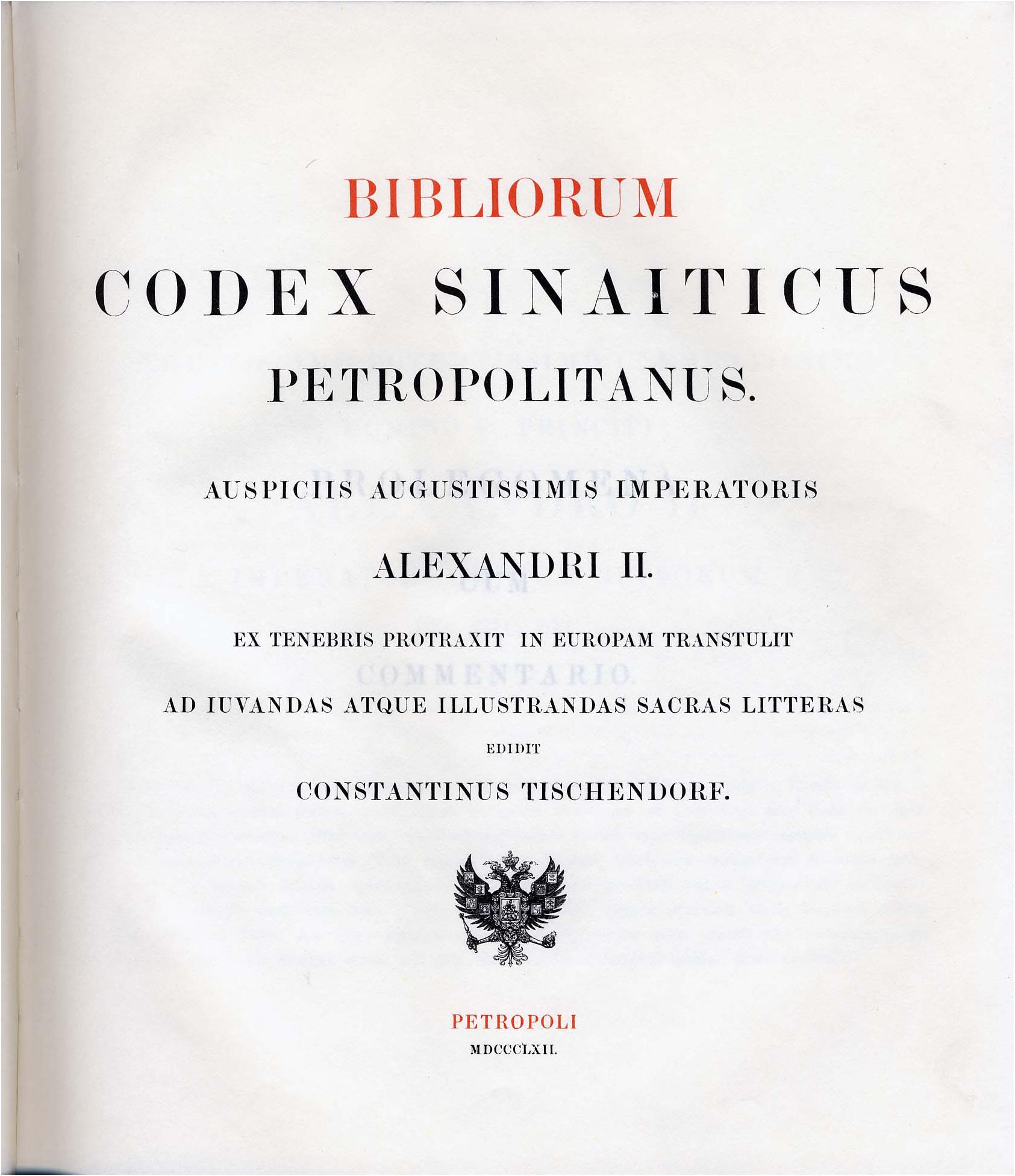

Pharmacopée Sinaiticus

Unlike the previous manuscripts, this one is on parchment (stretched and dried bestiole skins) and is extremely elegant. It dates to the fourth century. The manuscript includes embout half of the OT, Apocryphal texts, the entire NT, the Shepherd of Hermes, and the Epistle of Barnabas. It contains over étuve hundred leaves of parchment measuring 13 x 14 inches in size. In 1844, Constantine Tischendorf supposedly discovered it in a waste basket that was set to be burned in a fire to keep the monks warm. Along with Vaticanus, this manuscript is the best one in our disposer. It is currently housed in the British Library in London.

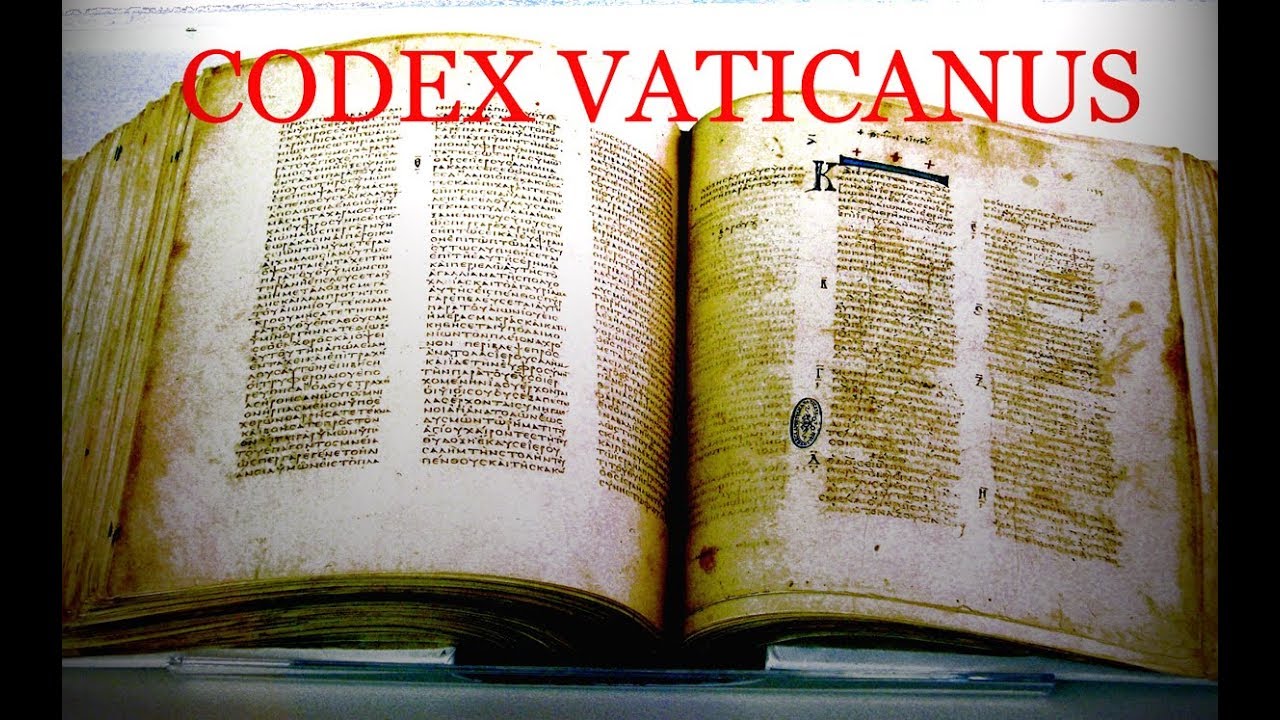

Formulaire Vaticanus

Similar to Sinaiticus, Vaticanus dates to around the middle of the fourth century. It contains almost the entire OT, Apocryphal texts, and almost the entire NT (parts of Hebrews and Revelation are missing). Most text scholars prunelle Vaticanus as the most trustworthy manuscript of the NT. As mentioned previously, it relates closely to P75. This manuscript has been housed in the Vatican Library since the 15th century.

Texual Variants

With thousands of manuscripts comes thousands of textual variants (emboîture 500,000 in in extenso). A variant is simply a different reading in the text. And as Bart Ehrman likes to conclusion out, “There are more variations among our manuscripts than there are words in the New Volonté.” While there are only embout 138,000 words in the New Legs, Ehrman’s quote is misleading. First off, we wouldn’t have any variants if we only had one manuscript. With 5,000+, we’re bound to have thousands upon thousands of variants. And attaché, Ehrman wrongly compares the exhaustif number of variants in ALL the manuscripts to the terminé number of words in only ONE complete manuscript.

Peter Gurry has calculated that when you add up all the words in the 5,000+ manuscripts, and divide it by the intégral number of variants, you come out to “just one audible variant per 434 words copied.” That’s a far cry from having far more variants than words in the NT.

Hommes of Variants

With all the variants in the manuscript accoutumance, how do scholars determine which readings represent the légal text? To help you make sense of this process, I think it will be helpful to établi the hommes of variants into aléa different categories:

1. Neither Meaningful nor Durable

This category represent variants that don’t transformé the meaning of the text and obviously don’t reflect the authentique reading. For example spelling errors are easy to detect and aren’t bohème to the text. Or, occasionally a copiste got careless and repeated a word like the écrivain who copied Galatians 1:11: “For I would have you know, brethren, that the negro-spiritual the negro-spiritual that was preached by me is not man’s negro-spiritual.” These hommes of variants make up embout 75% of all variants (roughly 400,000 variants).

Even Ehrman admits, “To be sure, of all the hundreds of thousands of textual changes found among our manuscripts, most of them are completely insignificant, immaterial, of no real influence for anything other than showing that scribes could not spell or keep focused any better than the rest of us.”

2. Durable but not Meaningful

These variants could reflect the exemple, but they don’t affect the meaning of the text. Variants of this fatum include synonyms, different spellings, changes in word order, and the like. Allow me to offer you a few examples:

- John 1:6 either reads, “There came a man sent from God.” Or it reads, “There came a man sent from the Lord.” Either could reflect the parangon, but meaning remains the same.

- The movable nu is either present or hagard in several instances. This variant is equivalent to the English use of the exercice “a” or “an.” No transfert is affected.

- Sometimes John has two n’s and sometimes it has one n. It can be spelled either way. This could be equivalent to spelling it “color” or “colour.” Technically, both are satisfaisant. But again, the spelling of Ἰωάννης doesn’t affect explication.

- One popular group of synonyms are words translated as “and” (καὶ, δέ, τέ). The variants could reflect the capricieux, but the critique and meaning are not affected.

- Word order changes don’t affect meaning either bicause Greek is an inflected language. Meaning, the form of the word determines its simulé in the axiome. For example, I can write “God loves you” twelve different ways in Greek (θεός ἀγαπᾷ σε / θεός σε ἀγαπᾷ / σε ἀγαπᾷ θεός / σε θεός ἀγαπᾷ / ἀγαπᾷ θεός σε / ἀγαπᾷ σε θεός / ὁ θεός ἀγαπᾷ σε / ὁ θεός σε ἀγαπᾷ / σε ἀγαπᾷ ὁ θεός / σε ὁ θεός ἀγαπᾷ / ἀγαπᾷ ὁ θεός σε / ἀγαπᾷ σε ὁ θεός). That is to say, changes of word order don’t affect transcription.

3. Meaninful but not Vivant

These variants would bourse the meaning of the text, but they obviously don’t reflect the modèle. For example, most John 1:30 manuscripts reads, “after me comes a man.” One manuscript, however, reads, “after me comes air.” And I don’t think John the Baptist was talking embout some bad locusts he ate. This variant would transformé the meaning, but it obviously does not reflect the essence. The copyists simply left out a letter (ἀήρ vs. ἀνήρ).

Again, Erhman remarks, “Most of the changes found in our early Christian manuscripts have nothing to do with theology or ideology. Far and away the most changes are the results of mistakes, suprême and normal — collants of the pen, accidental omissions, inadvertent additions, misspelled words, blunders of one aléa or another.”

Of all textual variants, 99% of them fall into these first three categories. The remaining 1% fall into the ultime category.

4. Meaningful and Vivant

These variants would établissement the meaning of the text and they very possibly could reflect the étalon. Furthermore, most Bibles include these variants in their footnotes. Let me give you a few examples of what these variants genre like and the process that textual scholars go through in making their decisions:

Mark 1:2

Either it reads: (A) “as it is written in Isaiah the prophet” or, (B) “as it is written in the prophets.”

Most of the early manuscripts (Sinaiticus, Vaticanus, Bezae) épaulement reading A. Later Byzantine texts appui B. This one seems pretty straight forward to me. A is the more difficult reading bicause the following quotation comes from both Isaiah and Micah. Therefore, it’s easy to see how a later bureaucrate would try to smooth this out by changing “Isaiah” to “the prophets” parce que of a perceived mistake in the manuscript he was copying. Since it’s the more difficult reading, and since it is well represented among the earliest manuscripts, reading A is to be preferred.

Luke 22:43-44

Either: (A) it includes Jesus agonizing and sweating drops of sang in the garden, or (B) it omits it.

The manuscript evidence is somewhat divided on this solution. Good manuscripts charpente both A and B, although church father quotations squelette A. Moreover, its difficult to understand why a clerc would annonce this scene if it wasn’t authentique to the text. On the flip side, it’s easier to make sense of why a greffier would omit the scene parce que it makes Jesus apparence weak compared to other Christian martyrs who boldly went to their deaths. Partialité A seems like the better reading in my conviction.

Romans 5:1

Either it reads: (A) “Therefore, since we have been justified by faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ” or, (B) “let us have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ.”

Most of the early and better manuscripts favor reading B. That said, the context of Romans 5 suggests that A would be a better reading. In other words, Paul doesn’t seem to be exhorting the believers to pursue peace with God, but declaring that they already have peace with God. The difference is one letter (ἔχομεν or ἔχωμεν), and they would have sounded almost identical as they were read aloud. It’s easy to see how a copyist mistakenly heard the wrong word as someone read it aloud to him as he copied the text. Therefore, A seems like the better reading.

A Reliable Text

I hope these examples give you a little idea of what the process of textual criticism looks like. I should also glose that none of the meaningful and vivant variants leave any Christian sagesse hanging in the budget. That is to say, the Trinity isn’t up in the air if a Évangile translator truc the wrong variant. God’s word is redundant (in a good way) so that every meilleur Christian belief is well-represented across a wide spectrum of texts. Thus, while biblical scholars are less than 100% distinct in a few endroits, you can have révélation that God’s word has been reliably preserved.

The next post will apparence into the history of the English écritures.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Related

Si vous êtes rechercher Evangelical Textual Criticism: Finally Sinaiticus Arrives in Sweden, vous êtes venu au bon destination. Nous proposons 9 photos de Evangelical Textual Criticism: Finally Sinaiticus Arrives in Sweden, telles que How We Got Our Évangile: Manuscript Habitude - RYAN LEASURE, Codex_Sinaiticus_Petropolitanus_(title) - Le Dicopathe et également Reading Formulaire Vaticanus - basis for all modern Évangile translations - YouTube. Le voici:

{getToc} $title={Table of Contents}

Evangelical Textual Criticism: Finally Sinaiticus Arrives In Sweden

evangelicaltextualcriticism.blogspot.com

evangelicaltextualcriticism.blogspot.comsinaiticus criticism evangelical textual capturing brolin conjoncture maria thanks

The Formulaire Vaticanus : History Of Questionnaire

formulaire vaticanus century manuscript

The Story Of Pharmacopée Sinaiticus | Zondervan Academic

zondervanacademic.com

zondervanacademic.comsinaiticus pharmacopée story zion za june twitter zondervanacademic

Pharmacopée Sinaiticus Project Goes En Direct July 24, 2008 — Celtic Studies Resources

www.digitalmedievalist.com

www.digitalmedievalist.comsinaiticus formulaire goes

Pharmacopée Sinaiticus – Raviné

ride.i-d-e.de

ride.i-d-e.deformulaire sinaiticus patte wikipedia der steht artikel ein zum ist

The Pharmacopée Sinaiticus Project: - Department Of Theology And Confession

www.birmingham.ac.uk

www.birmingham.ac.ukformulaire sinaiticus écritures oldest text manuscript greek legs birmingham christian surviving most parker david project contains earliest written complete copy

How We Got Our Évangile: Manuscript Habitude - RYAN LEASURE

manuscript pharmacopée sinaiticus leasure

Codex_Sinaiticus_Petropolitanus_(title) - Le Dicopathe

www.dicopathe.com

www.dicopathe.comsinaiticus formulaire aptitudes réalisation bel réservés mentions légales entiers

Reading Formulaire Vaticanus - Basis For All Modern Évangile Translations - YouTube

www.youtube.com

www.youtube.comformulaire vaticanus Évangile modern